Founder of Your Agora, educator, writer

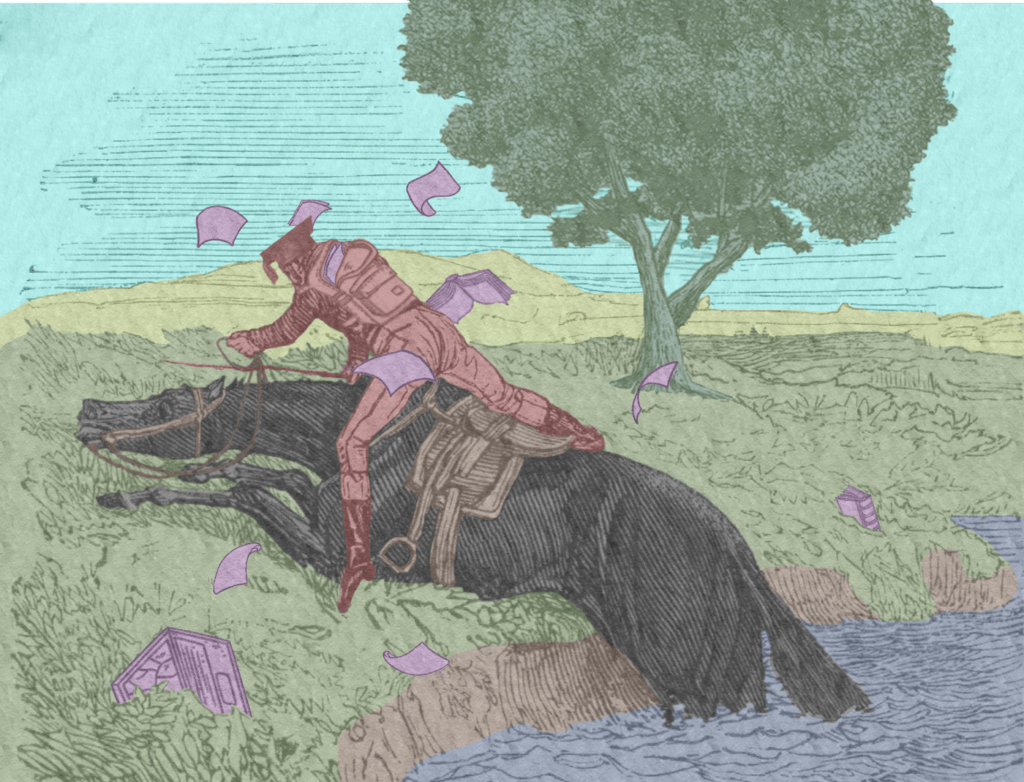

There is an apocryphal quote attributed to Henry Ford that goes, “If I had asked my customers what they wanted, they would have told me a faster horse.”1 It’s the kind of thing “disruptors” like to say as it reinforces their sense of being visionaries able to see what their critics can’t. So how is one to tell what is truly innovative thinking? A good starting point is to consider how well the current solutions and paradigms are working. What will be argued here is that education is now at a point where improvements within the existing framework are seeing diminishing returns. Education needs to leap forward, and our current horses are not up to the challenge.

As industrial nations move into post-industrial economies, educational imperatives are changing. The baseline knowledge to be a functioning citizen is higher.2 You’re probably going to need at least a little algebra, computer skills, and a second language to get by, for example, unlike previous generations that could suffice with arithmetic and basic reading. An increasingly higher percentage of better paying entry-level jobs are also only obtainable through certifications and diplomas available through universities, colleges, and trade schools.3 The best-paying jobs often require highly specialized knowledge and skills, which take years of studying and practice before they can be applied on the job, and there aren’t enough applicants to fill them.4

The preparation of children and young adults for work is only half of the story, though. Education continues to play a critical role in shaping a child’s identity and teaching them the values of their society. Learning how to socialize and properly navigate an increasingly complex world is also of critical importance, as is giving students the time to experiment with some of the thousands of possibilities, both personal and professional, now available to them to find the best fit for their interests and talents.

Our educational institutions are now ill-equipped to handle all these new requirements, and proposed solutions often double down and rebrand an antiquated paradigm. The current methods of education rely heavily on standardized courses with standardized assessment.5 This worked well when knowledge and skills were simple, and the regression to the mean was acceptable. Now, however, there is more to learn than students can master, and the need for students to excel, regardless of acuity, is critical for a diverse society and a sufficiently specialized workforce. Schools and institutions can no longer afford to give up on underperforming students while overperforming students are not adequately challenged or differentiated. Ask any school teacher the frustrations of “teaching to the test” or any university admissions professional how difficult it is to pick the best students when they all have identical GPAs and SAT scores and you will begin to understand the severity of this problem from both ends.6 7

Teachers are doing their best, and the best teachers are doing incredible things. However, working within programs that treat students as uniform, industrial batches makes progress an uphill battle. And what is the typical solution? More tests, more courses, and more material. Putting everything online is also supposed to make things better somehow. For a time, everyone thought MOOCs were going to change education, and look how that turned out.8 Universities as prestigious as Havard are now offering fully online master’s degrees, but the quality and lack of teacher involvement have led to accusations of these programs being scams.9 Even when teachers remain involved, the result is usually a static pdf, video, activity, or game, all of which the teachers have to shoehorn in with their existing books and spend countless hours managing, reporting on, and shuffling between.10 Integrating AI to automate the process would be a break in the paradigm, but the technology is premature and doesn’t work very well, providing as many headaches as solutions.11 Considering teachers are one of the least likely professions where automation is likely to be practical, that shouldn’t be surprising.12 There has to be a better way, and there is.

The way forward rests in trusting the ability of teachers to understand and meet the needs of their students and in giving them the tools and latitude to do so. A teacher must be able to take the content of their course and adapt it to their students’ particular needs and interests. Standards are still essential but meeting those standards cannot be the only goal. A greater variety of material in more interactive forms is a step in the right direction but only to the extent that the teacher can determine what is working and what isn’t and can improve the material based on those results. The content of the course itself must align with the realities that only the teacher fully grasps. This is doable but not through the typical tools on offer. Even with appropriate tools, it will only work when teachers and administrators have a fundamentally different understanding of, expectation for, and interaction with them.

Who am I to say this? Well, I’m certainly not a neutral party. I began teaching in 2007, and since then, I have tutored privately, taught middle school, worked for ESL Institutes, and guest-lectured at a university. My students have ranged in age from five to sixty-five. I have also, with help, built a platform specializing in developing, curating, and managing educational material. So, yeah, well acquainted with these problems but not neutral. That said, I’m also not here to blithely criticize.

We at Your Agora are frequently on a call with a potential client, and we find ourselves selling a solution to a problem the client hasn’t fully grasped the severity of. Whether you are teaching children or adults, English as a second language or Greek Philosophy, what is most critical is that your material can grow and adapt just as the students and teachers do. Accomplishing that requires not only the right tools but also a whole new way of thinking about and using those tools. Teachers get this, but the burden of change is high and mostly on them, which engenders fear and recalcitrance.

To continuously meet the developing needs of educators, Your Agora uses an iterative or “agile” approach that is now the norm in application design and development.13 Our vision is to bring that same approach to our clients and their educational materials. Putting this into practice means supplying a platform that provides teachers with the tools to control their material effectively and the metrics to determine what is working and what is not. Taking an iterative approach to educational content development and management also means providing material based on need and ability and building from there. A teacher can, for example, start a course with a few quizzes or supplementary resources and later expand to homework or classwork as needed. Or, a school could start with a self-study course and later add lesson plans to make the course teacher-guided.

Implementing such an approach does require additional work, but it is work that teachers are well equipped to handle if given the support and latitude to do so from their administrations. It is also work that pays off in spades once begun. Unfortunately, the alternative is beating a dead horse.